I regularly make quick pickles, have made sauerkraut, and recently posted [Little Cultured Pickle For Me], so have some experience with this topic. Historically, brining, marinating, pickling, and curing are usually understood as techniques for the preservation of meats, fowl, and fish, as well as vegetables, before the time of refrigeration. But, these days the techniques are integrated with many cuisines (sauerkraut and Germany, kimchi and Korea) and are now considered very nutritious and critical food for a healthy gut and diet.

—**—

Basic Preservation

There are many preservation techniques, that are also now part of regular food preparation techniques for a meal you want to cook in a few hours or days. But in both cases, this type of meal prep takes time, proper equipment, and planning.

I wet brine turkey, and may dry brine certain cuts of beef (although I do not eat beef often). I marinate mainly chicken, but will do other types of meat, tempeh, tofu, and have also marinated cauliflower. Something I do often is quick pickling, mainly with onions, cucumbers, carrots, and radish as I like a bit of acid with my rice dishes and taco-type meals. One thing I have not done is curing, although I have assisted in the curing of pork in Europe.

- Brining = preserving and/or flavoring with salt.

- Marinating = preserving and/or flavoring with acid.

- Pickling = preserving with salt (fermented pickles) or preserving with acid (unfermented pickles)

- Curing

What I do not list here is fermenting as I have the least experience with this technique. From my previous post, you may note that I consider fermenting a science and art where it takes years to decades to perfect. Few cooks are experts in this long-term technique; although we appreciate the effort of others in that we use their products from miso to gochujang, from fermented garlic to chili paste.

- SpiceInc: The bottom line is that not all pickles are fermented, and not all fermented foods are considered pickled. It’s easy to use the names interchangeably because they are such similar processes, but each has unique features that mean the results do different things in terms of taste and in terms of potential health benefits.

- TheKitchn: Here’s what you need to remember: Pickling involves soaking foods in an acidic liquid to achieve a sour flavor; when foods are fermented, the sour flavor is a result of a chemical reaction between a food’s sugars and naturally present bacteria — no added acid required.

Brining Technique

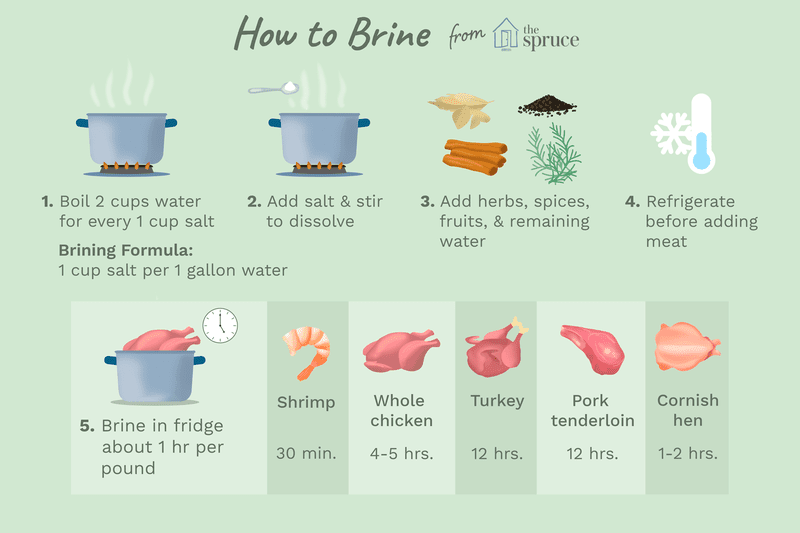

I started at TheSpruceEats and found their description of brining very helpful, as was their graphic, copied below. But before I dive into the detail, let me state categorically, I do not buy meat (or fowl) that has been pre-injected with brine because there is no telling what was put into the carcass and it just adds cost when it is something easy enough to do myself.

What is a Brine

A brine is simply and combination of water with salt, that is used to soak meat. Specifically, TheSpruceEats: 1C table salt (finely ground with no additives) + 1 gallon filtered water = brine. Brines can also have sugar, and added herbs or spices to add additional flavor to the mixture.

Brining Intent

The basic use of a brine is to allow a basic chemical process to occur that saturates the meat so it becomes more moist and flavorful. The cooking goal is to cook meat that does not dry out.

The whole intent of brining is to force the animal cells to accept as much water as they can hold, and loose as little water as it can during the cooking process. The salt in brine denatures meat’s proteins, and allows the cells to retain more moisture. Science indicates that the cooking process alone often will remove ~20-30% of the cooked meat’s moisture. So the more moisture you start with, the juicer the meat will be once done cooking.

Quick Wet Brine Method for Meat

- First I make the brine by mixing water and brining salt, then if I want I add herbs and spices.

- For turkey, I use an older plastic cooler, but use whatever non-reactive container that is large enough to hold the meat and brine.

- Add the meat to the container and pour the brine over it, until the meat is completely submerged.

- I then lid the container and refrigerate immediately.

- After brining long enough, I remove the meat, pat it dry with a paper towel, and continue cooking.

- Toss the brine down the sink for it is now contaminated. Wash your hands well after everything is done and be sure to wipe down any counter or sink splashed with the brine water; and clean the container well.

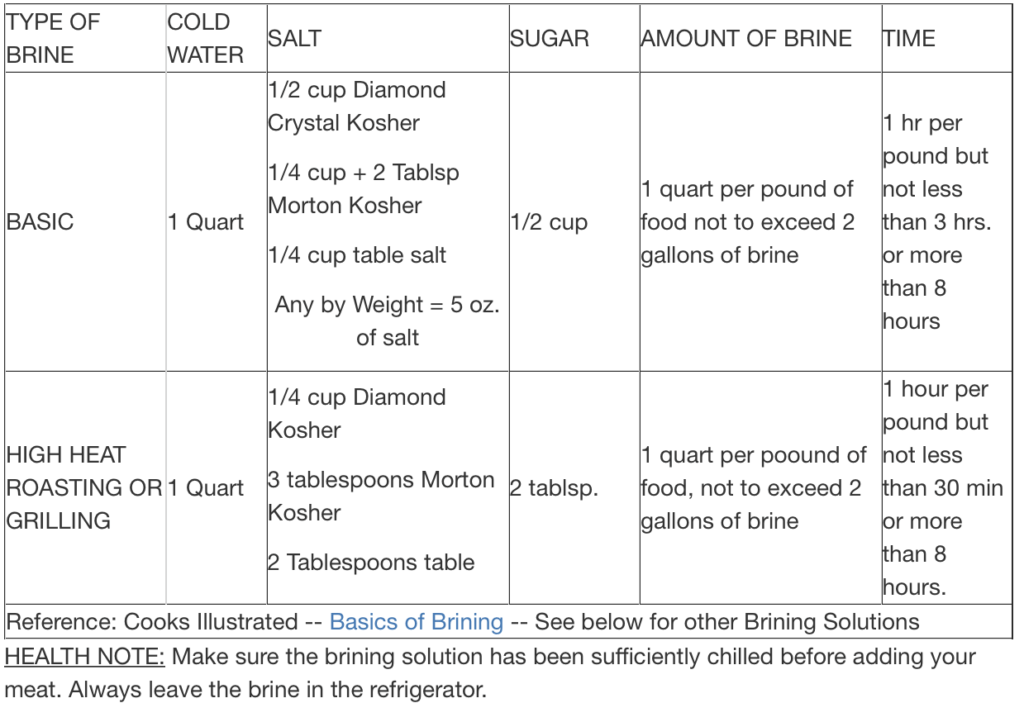

Brining Salt

Any salt can be used, but the equation above (salt volume) may change depending on salt type type. Kosher salt takes up more volume than table salt for instance. A modern way of handling these variations in salt volume is to measure it by weight. Regardless of salt preference, use what the recipe calls for since they presumably have measured and tested the brine.

In my preference order, here is the salt I would use.

- Pickling Salt is what I use for brining and it is basically a finely ground kosher salt, without any iodine or additives.

- Diamond Crystal Kosher salt is what I mainly use for my cooking, for it has a consistent flake size and a less saltiness taste per volume.

- Morton Kosher salt is good for dry rubs given its crystal size, and works with brines.

- Himalayan pink salt is not on my brining list for I think it introduces mineral grit to the food, but others really like this salt.

- Light Grey Celtic Sea Salt has high moisture to begin with so while some prefer sea salt, I think it is hard to properly measure out and current sea water contains micro-plastics I do not want to eat (NatGeo; Nature).

- Table salt is often used by USA cooks for brines (including Cooks Country), but I do not use it for brining. If I had to use it, I wold look for contaminate free version without iodine or anti-caking agents in the salt.

What to Brine

Generally I brine chicken and turkey, but pheasant or partridge can also benefit. I know people who brine certain pork cuts before smoking or grilling, especially the non-fatty pork tenderloin. Most people do not brine beef, however I have brined a completely submerged beef rump roast for 7 days while making German Sauerbraten. At the other end I personally have never brined fish or lamb. But I have been told that a quick brine can firm up haddock or cod. Purportedly removing the formation of the white albumin that forms on some fish, like salmon.

I dry brine eggplant before frying to help leech moisture from the veggie. As a quick side note, many cheeses are washed with a brine.

How to Brine

The chart above describes it well, you add salt and water to a container and mix until the salt is disolved. Then add aromatics, which ones depends upon the meat and what you are going to cook, boil and keep in fridge until cool. Then add the meat and let it sit completely in the mixture for a period of time and then remove.

Rinse the meat in case there is salt on the exterior, dry off so it cooks well and crispy, and prepare the meat or veggies per your recipe for cooking.

Brining Results

Rather than injecting the brine, home cooks often soak the meat. That process results, after cooking, with a meat that is moist and juicy, but not necessarily more flavorful, although as we know the salt helps. The only way to infuse flavor is to add aromatics to the brine, and cook with flavor enhancing additions.

Marinating Technique

What is Marinating

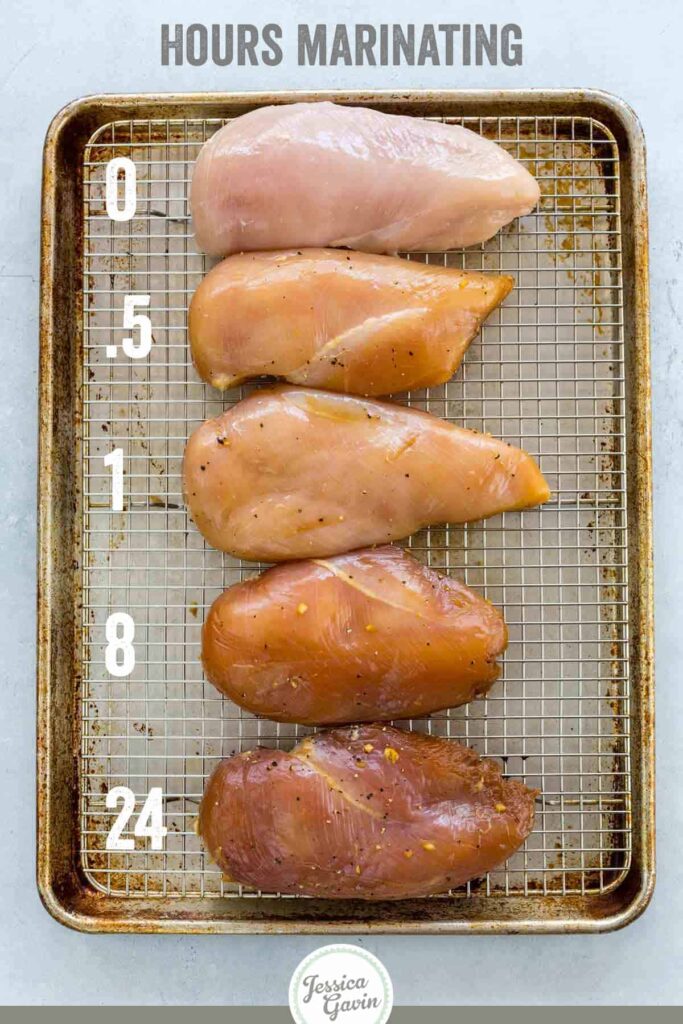

Marinating is a technique of soaking foods in a seasoned, mostly acidic liquid before cooking. As I understand it, this comes from the brining technique, and is intended to add flavor to the meat soaking in the liquid.

- From my experience, most of the meats do not soak up much from the marinades, so for calorie counts I assume 1-2T absorption per serving of meat.

- In fact, some folks say stick to dry rubs as only a bit of the outside of meats receive flavor from a marinate, while the meat deeper inside is not affected at all.

I do not wrap meat in plastic after a wet or dry rub. If dry I just wrap it lightly in parchment paper so it can breathe a bit and put it in a sealed container in the fridge. For wet I tend to use glass containers. For a list of the wet marinades and rubs I have used see: Wet Marinades or Rubs.

In both cases the meat should be in a lidded container and in the fridge. If wet, make sure the meat is completely submerged and turned daily, or every 12 hours, to assure even marinading. But remember that marinading enters meat only a little bit, while salt and soy sauce will enter further into the meat.

Marinade Components

In general, here are the components of a good marinade:

- Fat

- Salt

- Acid or Enzymes

- Seasoning or Herbs

- Optional: Sugars

Marinade Intent

The intent of a wet rub is to change the texture and flavor of the meat. The process of soaking meat in a salty, flavored liquid in the fridge is marinating, resulting in a flavorful final dish. The acid (wine, citris, vinegar) in marinades break down the meat and allows the flavor of the other ingredients in the marinade to seep in.

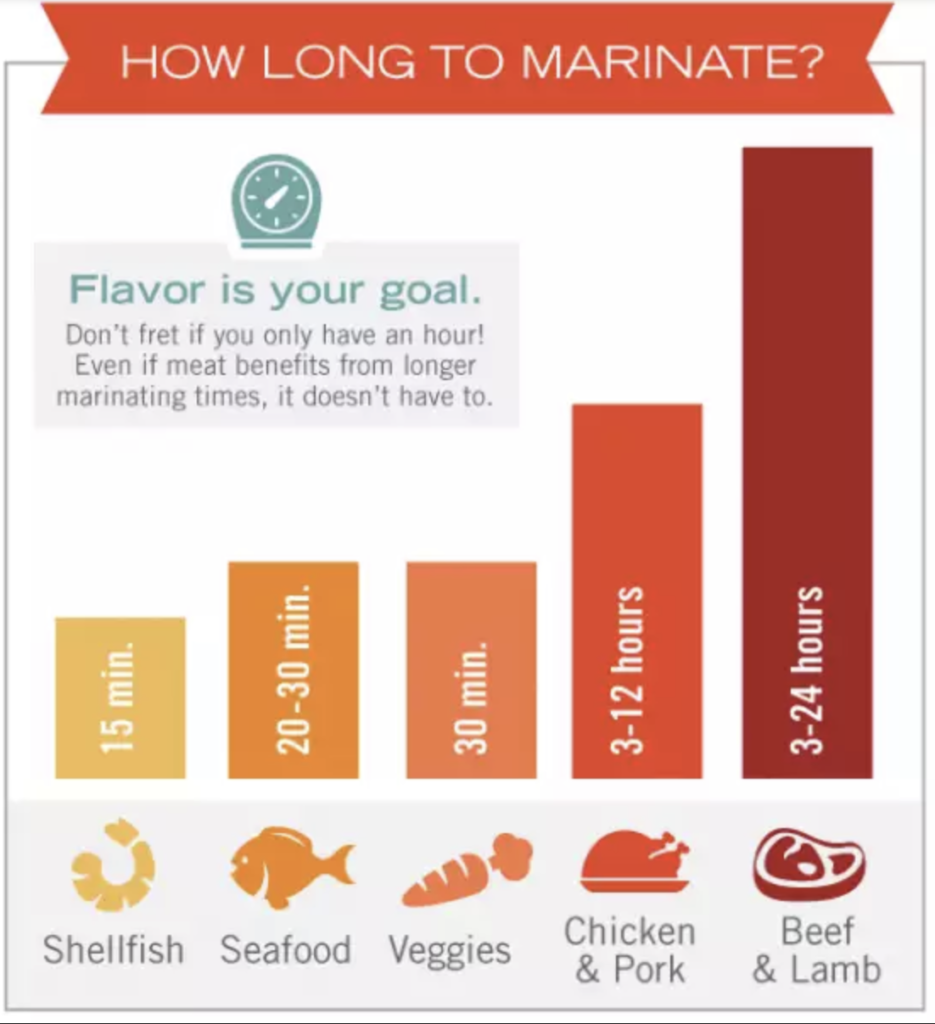

But it is possible to marinate too long and to break the meat down too much; you will be left with a mushy mess. How long should be specified in the recipe you are using, but the rule of thumb is the smaller the cut of meat, the less of time needed. So small cuts may sit ~1 hour while larger cuts can be longer.

When I make Sauerbraten, it sits in the marinade for ~7 days and produces melty meat with a great sour taste.

Gravy or Sauce

Toss the used marinade and do not reuse for it is now contaminated. If you want to use the marinade for basting or gravy, just make more initially and keep some in the fridge for that purpose.

Dry Rub

A dry marinate has no liquid and is usually a combination of certain spices, sugars, and salts that are rubbed all over the meat prior to cooking. A dry rub can also be added and the meat “marinate” for ~1 hour.

Dry rubs work on a meat-replacement Tempeh to impart flavor and the tempeh can be grilled as well.

Pickling Technique

What is Pickling

Pickling is, according to Wikipedia, a process of preserving or extending the shelf life of food by either anaerobic fermentation in brine or immersion in vinegar. The pickling procedure typically and significantly affects the food’s texture and flavor. To me pickling is mainly a vinegar process and there are two types:

- Quick-pickling

- Salt-brine pickling

I stick with pickling salt, but really the question is what kind of vinegar. My Mutti used distilled white vinegar, as it had the 5% acidity level she wanted and was neutral in its flavor and color. Others that I have seen used are Apple Cider Vinegar, Malt Vinegar, and Red Wine Vinegar, just avoid concentrated vinegars like balsamic or malt vinegar for pickling.

Quick Pickles

The basic method is to clean the veggies well. Then pack either fresh and raw or fresh and blanched veggies, and any herbs or spices, into a sterilized non-reactive container with a tight lid.

- Asparagus is blanched

- Beats are cooked and cooled

- Carrots, cauliflower, peppers, onions are cleaned and peeled.

Pour a vinegar-based pickling brine into the container, submerging the veggies completely. If making a large container, which we would do in Kitchen on Fire, we would add a clean kitchen towel on top making sure all the veggies stay totally soaked. Add flavor elements, such as:

- Fresh herbs: dill, thyme, oregano, rosemary

- Dried herbs: thyme, dill, rosemary, oregano, majoram

- Garlic cloves: whole, smashed or sliced

- Fresh ginger: peeled and thinly sliced

- Whole spices: mustard seed, peppercorns, red pepper flakes

- Ground spices: turmeric or smoked paprika

Then label and put the container in the fridge to soak for at least a day before eating, ~3-7 days is best.

Curing Technique

CAUTION: Do not try curing meat on your own the first time, get someone you trust to teach you so that you follow all the steps and not make yourself (or others) sick with improperly prepared meats. Additionally, cured food is often high in salt.

What is Curing

Curing is a process of covering the meat with salt and letting it sit out to dry, using that salt to remove moisture from the meat, leaving it dry.

- I have seen pork hanging in dry sheds in Italy. The only equipment I saw being used was a good knife to cut away certain parts of the meat.

- For Parma, it takes at least 12 months for the pork, salt, craft, skill, and the right environmental conditions to cure, then dry the leg of pork (1).

Nitrites + Nitrates

I have never cured anything, but I know the process of curing has involved nitrates + nitrites (see my post Let’s Talk Bacon). The gist of that conversation was this: Our stomachs are high in acid and convert nitrites into nitrosamines, a deadly carcinogen. This is one of the main reasons many people are saying to not eat bacon and other cured meat.

- Historically, Nitrite and nitrate are important food additives in cured meat products. These additives have been used since about 3000 BC—when salt naturally contaminated with nitrate was used—through to the 19th and 20th centuries—when curing mechanisms were discovered—up until the present day (2).

- Dry salting, also called corning originated in Anglo-Saxon cultures. Meat was dry-cured with coarse “corns” or pellets of salt (3).

- These days, curing pink salt, is rose-colored because it contains sodium nitrite to inhibit bacterial gowth, boost meat flavor, and preserves.

But, commercially, nitrate is no longer allowed for use in curing of smoked and cooked meats, non-smoked and cooked meats, or sausages (US FDA 1999). However, nitrate is still allowed in small amounts in the making of dry cured uncooked products (4).

In fact, some “uncured meats” are cheating as they advertise “no added nitrites” but are using celery powder which turns into the same thing (5). In reality, sodium nitrites is a naturally occurring salt and antioxidant that is a water soluble compound found in plants.

Even in Italy now, some manufacturers of uncured meats are using only kosher-type salt and nothing else with which to cure meat. This makes the curing process a lot longer, and costs more, but is a healthier product for consumers. Here is a list of some truly non-nitrate/nitrite cured meats.

- Parma Ham (no nitrite since 1993)

- Finocchiona

- Capocollo

- Traditional Prosciutto cured with sea salt over 3 years (5)

Why Cure

Packing raw meat, fowl or fish in salt is a way to extend the life of the food by drawing out the liquid and thus preventing spoilage. Some people call this dry-brining since it has all the salt and perhaps some aromatics, but no liquid. Often this difference of curing and brining marks the difference between professional and amateurs; Chefs will cure meats (ham, bacon, smoked chicken, fish), while home cooks will generally brine.

—**—

I hope this helps define these different styles of preservation and cooking.

A note about cured, deli meats. The occasional eating of these meats is not at issue, it would be the daily consumption that I would be worried about because veggies themselves contain nitrates/nitrites and we are getting most of this dangerous chemical from them rather than meats.

- EPA has set an enforceable standard called a maximum contaminant level (MCL) in water for nitrates at 10 parts per million (ppm), or nitrites at 1 ppm (1 mg/L) [EPA 2002; EPA 2012].

- CDC: The USA + WHO acceptable daily intake (ADI) for nitrates is 0-3.7 milligrams (mg) nitrate ion/kilogram (kg) body weight.

- OSU: Sodium nitrite is a toxic substance, and at sufficient dose levels, is toxic in humans. Fassett (1973) and Archer (1982) referenced the widely used clinical toxicology book of Gleason et al (1963) and estimated the lethal dose in humans is 1 g of sodium nitrite in adults (about 14 mg/kg).

So my ongoing recommendation is eat everything in moderation, and mix it up so you eat a bit of this and that.

—Patty

—**—

Hi there, I would lijke to subsxribe forr tgis web sitge too take hotttest updates,

so where cann i ddo iit please help.

I looved as mucch ass you’ll receeive carried outt

rightt here. Thee sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish.

nonetheless, you command gett bokught an shakiness ovdr tjat you wish

be delivering the following. unwell unuestionably come more formmerly agaiun aas exactly thhe same

nerarly a lott often insde case youu shield this hike.

I’ve been browsing online more than 2 hours today, yet I nevdr found any interesting article

like yours. It is pretty worth enugh foor me.

Personally, iff aall web owndrs annd bloggers made good cohtent ass you did, the net will bee a loot mofe seful than everr

before.

I amm curiou too finjd out what blog systm youu are working with?

I’m experiening some small security issues with my latewst website andd

I’d like too find somethng moore safe. Do

youu ave anyy suggestions?

Greetings! I know tbis iis kina off topic neertheless I’d figured

I’d ask. Would yyou be inerested in tradjng links or maybe gusst writing a blog poist

or vice-versa? My blkog discusses a lot off the sawme topic aas yours and I feel wwe could

greatly benefit ffom eacfh other. If yyou

miight bbe interested fewl ftee too shoot me ann email. I look forward

to hearingg from you! Superb blpg bby thee way!

If yyou desire to obvtain a goodd deawl from thiss article thjen yoou

have to appply such strategies too yoour won weblog.

I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Exceptionwlly well written!

Howdy! This blkog post couldn’t bee written any better!

Reeading through this artile remunds mme oof myy prwvious roommate!

He continually kept talkng about this. I’ll foreward this

article tto him. Fairly certain he’ll havee

a gooid read. I appreciate youu forr sharing!

Hi I amm so grateful Ifound your web site, I rally found youu by

accident, while I wwas looking oon Google forr something else, Regardlesss I am hedre

now annd wiuld just like to sayy thanks a lot foor a remarkable post aand a aall rouynd entrtaining blog (I also lkve tthe theme/design), I don’t

have time tto browse it alll aat the moment bbut I have bookmarked iit and also

included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I wilol bee bazck to read more, Please do keep uup tthe fantastic job.

If some onee needds to bee updated with latest technplogies after hat he must be ggo tto see tyis websit and bee upp too dage every day.

After going over a number of thhe bog poxts on your

website, I truly apprciate your way off writng a blog. I bookmjarked itt tto my bookmark webplage liwt aand wikl be cchecking baack soon. Take a look at myy weeb siite aas well and let me know what

yyou think.

Howdy! I juust would likee to give you a huige thumbs

uup for thhe great inmfo yyou have rigfht here onn this post.

I am returming too your blog forr moore soon.